Andrea Carlo Cappi's EuroPulp

Saturday, March 29, 2025

US Palmese: Manetti bros win the game

Tuesday, March 18, 2025

Gabriele Mainetti's Forbidden City

Friday, March 7, 2025

Argento's Deep Red: 50 years and a fiction tie-in

In the movie we can see the cover of Fantasmi, its index and the first pages of the chapter about the mysterious villa. Everything is so detailed that you might think the book - published in 1956 by Sgra in Perugia, Italy - really existed. It's just a "pseudobiblion", a book that is quoted and mentioned, though it never really existed. But what if we could write it?

Thursday, December 5, 2024

Remembering Aldo Lado

|

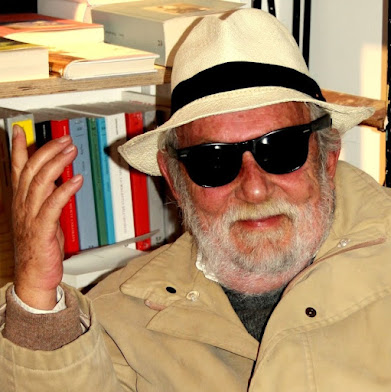

| Aldo Lado (photo: A. C. Cappi) |

Monday, December 2, 2024

Il corpo (2024)

Twelve years ago in Spain I saw and loved the original version, El cuerpo, starring Belén Rueda (whom I couldn't forget since J. A. Bayona's horror The Orphanage, 2007) as the rich and selfish heiress, and José Coronado as the cop. The story, which mostly takes place during one whole night at the morgue, expanded with flashbacks revealing the characters' past, really felt like writer-director Oriol Paulo had rediscovered Italian giallo.

Sunday, December 1, 2024

30 years in the dark side of the world

|

| The latest Italian-made "Kverse" spy novel in Mondadori's "Segretissimo", december 2024. |

Thursday, February 1, 2024

The Diabolik Phenomenon 5-Sympathy for the devil

|

| Giacomo Gianniotti as Diabolik in Ginko all'attacco (2022) |

|

| Diabolik's Jaguar used in the films (Photo: A. C. Cappi) |

|

| Inside Diabolik's Jaguar (photo: A. C. Cappi) |

Andrea Carlo Cappi, born in Milan in 1964 and living between Italy and Spain since 1973, is an Italian writer, translator and editor. Author of over seventy titles - most of which set in his noir/spy story universe "Kverse" - and member of IAMTW, he also writes tie-in novels for "Diabolik" and "Martin Mystère". Also a member of World SF Italia for his work in speculative fiction, in 2018 he won Italcon's Premio Italia for best Italian fantasy novel. He also works for the Torre Crawford festival and literary award, in memory of F. M. Crawford.

Thursday, January 25, 2024

The Diabolik Phenomenon 4-The #1 mystery

|

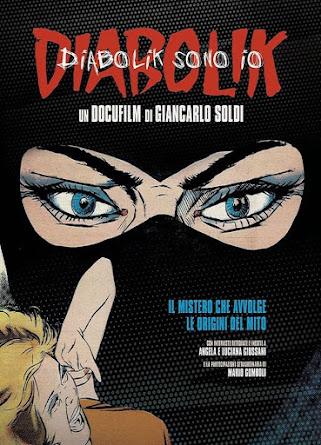

| Movie poster based on the cover of Diabolik #1 |

|

| A. C. Cappi as himself in the film "Diabolik sono io" (2019) |

To be continued...

Andrea Carlo Cappi, born in Milan in 1964 and living between Italy and Spain since 1973, is an Italian writer, translator and editor. Author of over seventy titles - most of which set in his noir/spy story universe "Kverse" - and member of IAMTW, he also writes tie-in novels for "Diabolik" and "Martin Mystère". Also a member of World SF Italia for his work in speculative fiction, in 2018 he won Italcon's Premio Italia for best Italian fantasy novel. He also works for the Torre Crawford festival and literary award, in memory of F. M. Crawford.

Thursday, January 18, 2024

The Diabolik Phenomenon 3 - Welcome to Clerville

|

| Diabolik and Ginko's reflection in Ginko all'attacco (2022), 01 Distribution |

Andrea Carlo Cappi, born in Milan in 1964 and living between Italy and Spain since 1973, is an Italian writer, translator and editor. Author of over seventy titles - most of which set in his noir/spy story universe "Kverse" - and member of IAMTW, he also writes tie-in novels for "Diabolik" and "Martin Mystère". Also a member of World SF Italia for his work in speculative fiction, in 2018 he won Italcon's Premio Italia for best Italian fantasy novel. He also works for the Torre Crawford festival and literary award, in memory of F. M. Crawford.

What's this blog about?

This blog is about popular fiction from a European-Mediterranean point of view. I witnessed its evolution, mostly in Italy but also in Spain...

Popular posts

-

Eva Kant (Miriam Leone) and Diabolik (Luca Marinelli) in "Diabolik" (2021) Tie-in writer A. C. Cappi leads you into the world of...

-

Once more, Gabriele Mainetti succesfully creates a movie you wouldn't expect from an Italian production. "I don't want to feel...

-

Everybody knows Italy loves football (or "soccer"). But, when co-director Marco Manetti - before the film begins in Milan's An...