|

| Diabolik and Ginko's reflection in Ginko all'attacco (2022), 01 Distribution |

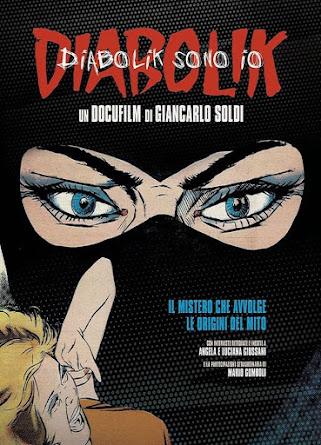

From a real life murder to a fictional world

Mystery and crime fiction have been succesful in Italy since 1929, as I already explained here. But, according to the fascist regime in power since 1922, no murder was supposed to happen in Mussolini’s ‘perfect’ country, so most of the few Italian mystery writers at the time had to set their detective stories elsewhere. In the end, readers were effectively convinced that no murder story could ever be set in Italy, therefore no Italian writer would be able to write a credible one, two ideas that would persist for a very, very long time. Later, the regime censored the whole of crime literature, anyway. The libri gialli were back on sale in 1946, in the newborn free and democratic Repubblica Italiana. But most Italian mystery writers still had to set their stories in US cities they had just read about in American hardboiled books, often hiding themselves behind foreign pen names. Anyway, in Italian language, the word giallo acquired the meaning of "real life unsolved mystery" as well.

When Angela and Luciana Giussani (who decided to sign themselves A. & L. Giussani, keeping their Italian identity) chose a thief and murderer who baffles the police as their new comics hero in 1962, they had two problems to solve: the name and the place.

|

| Art by Riccardo Nunziati |

In 1955 audiences world-wide were shocked by Les diaboliques, H. G. Clouzot’s movie based on a thriller by French mystery writers Boileau and Narcejac. The word diabolico became associated with murder... and terror: in 1957 Italian journalist Italo Fasan, under the unlikely pen name 'Bill Skyline', published one of the many gialli you could find in newsstands from minor publishers, a fake-American thriller titled Uccidevano di notte (‘They killed by night’) featuring a serial killer who writes letters to the police signing himself ‘Diabolic’. In 1958 a real life murder in Turin hit the news: the perpetrator sent the police a letter signed ‘Diabolich’ (with a final h), possibly inspired by Fasan’s novel. The book was immediately republished under the title Diabolic-Uccidevano di notte, this time with the author's real name proudly on the cover. Diabolich would never be discovered. In early 1962, famous Italian comedian Totò appeared in various roles in the crime spoof film Totò Diabolicus, inspired by the 1949 British movie Kind Hearts and Coronets.

All this events probably inspired Angela and Luciana's choice of the name ‘Diabolik’, with a final k - unusual in Italian language - giving it both an exotic and ‘evil’ sound. But where would Diabolik commit his crimes?

|

| Clerville State map appearing in the films |

At first Angela and Luciana Giussani thought about using Paris and Marseille as a setting, but soon they shifted to the fictional cities of Clerville and Ghenf, in the equally fictional European state of Clerville. This simplified work in the art department: no need to draw the Eiffel Tower in the background, for instance. Besides, no Italian policeman would be offended, since cops always seem unable to defeat Diabolik. A similar choice had been made in his novel El inocente (1953) by Spanish writer Mario Lacruz, who could not criticize the police in his country under Franco's regime; or by American writer Evan Hunter (born Salvatore Lombino) under his pen name 'Ed McBain' in his police procedural 87th Precinct series (1956-2005) set in the fictional US city of Isola, just because this allowed him more leeway in his stories then the real New York City.

After all, fictional cities like Metropolis or Gotham City had already appeared in DC Comics such as Batman and Superman. Half a century later this would lead to a detailed tourist guidebook (the brilliant Guida turistica di Clerville), complete with a Clerville city map and a Clerville State road map, which are now used as a reference book: for instance, the streets and squares mentioned in the opening chase of the film Diabolik (2020) strictly follow the city map.

But Diabolik goes far beyond. A whole brand new geography would be created, with fictional countries surrounding the State of Clerville, and more fictional countries all around the planet. In over sixty years, Diabolik and Eva Kant’s adventures would mostly take place in an alternative world. My personal contributions have been baptising ‘Gau Long’ a previously nameless Hong Kong-like city in the Far East, and establish ‘Zlata’ (inspired by Praha) as the capital of the Republic of Rennert: in the movie Diabolik-Ginko all’attacco you can find both cities in the departure list at Clerville Airport. The only exceptions to this "other world" in the comics are recent occasional short stories set in real Italian cities, published for comics conventions or special events.

|

| One of the Jaguar E-Types used in the films |

As it often happens with long-lasting series, time also flows differently in this world: characters are not allowed to age, or rather, they do it very slowly, while objects around change according to real life technology. Diabolik still drives his 1961 Jaguar E-Type, but cell phones and computers have appeared in the comics and Clerville has adopted euro as a currency, along with many real Euopean countries. The rule is: four years in the readers’ reality are just one year in the characters’ lives, so sixty years of comics are actually fifteen years for Diabolik, Eva and all the others. In this time, they have evolved somehow – as it would be natural in fifteen years – but have not been altered. Stories are still essentially capers, a subgenre not overexploited (unlike psychthrillers, for instance) and not so easy to write, which makes stories very interesting to read.

When Marco e Antonio Manetti turned into movies three classic episodes of Diabolik comics from the Sixties, they decided to remain closer to the time in which they had been written, just moving the stories slightly forward, between the end of the Sixties and the beginning of the Seventies. So not only in the films you can find cars, objects and clothing dating back to 1968-72, but also the look and the flavour of the movies of those times: while Diabolik (2020) has a few hitchcockian notes, Diabolik - Who are you? (2023) recalls Italian police movies of the early Seventies.

But there’s more to be discovered in the world of Diabolik, including another real life mystery behind issue #1.

To be continued...

Read also

The Diabolik Phenomenon 5 - Sympathy for the devil

Andrea Carlo Cappi, born in Milan in 1964 and living between Italy and Spain since 1973, is an Italian writer, translator and editor. Author of over seventy titles - most of which set in his noir/spy story universe "Kverse" - and member of IAMTW, he also writes tie-in novels for "Diabolik" and "Martin Mystère". Also a member of World SF Italia for his work in speculative fiction, in 2018 he won Italcon's Premio Italia for best Italian fantasy novel. He also works for the Torre Crawford festival and literary award, in memory of F. M. Crawford.